“To teach students to write compellingly, we must give them compelling reasons to write.” – D. Warlick, Redefining Literacy 2.0

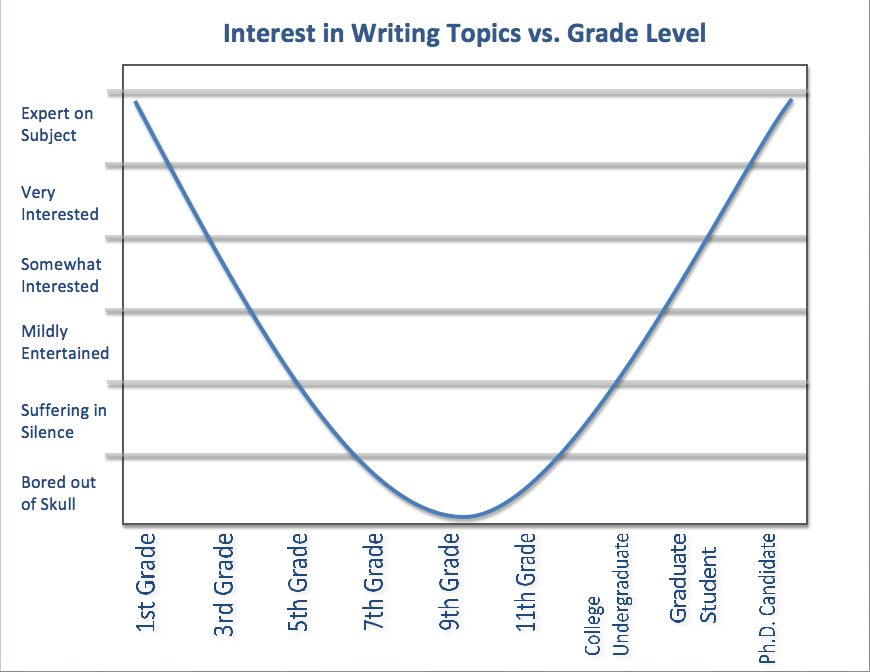

I see writing in the milieu of academia as an inverse bell curve or a parabolic curve. With interest in subject matter on the vertical axis and grade level on the horizontal, a very large majority of the writing our students do is on subjects in which they have little to no interest. To a first grader, writing an essay on “What I did last summer” is the most engaging writing he’s ever done. Likewise, to a biology Ph.D. candidate, writing his doctoral dissertation on “The effects of negative ions on the reproduction cycle of Brazilian Tree Frogs” is equally engaging. However, if you ask a high school freshman to write an essay on “In The Great Gatsby, in what ways are Wilson and Gatsby similar?” that student could not really care any less about what he’s writing about.

Warlick’s statement about “compelling reasons to write” is so painfully obvious when expressed in this manner that it is hard to imagine how we ever let education reach this point. If, as a teacher, you really want the student to be able to express in what ways Wilson and Gatsby are similar, maybe you should put some thought into whether an essay is the best way to express his opinion. Maybe let the student produce a video or even (gasp!) a bulleted list about that topic, but then let the student write an essay on something that is more interesting to him. Perhaps he loved the cars in the book and found that interesting. As long as the student is actively engaged in the subject, does it truly matter what he chooses to write about? In the “real world,” some people are fascinated by the mechanics of how a car works, some love the shape on the outside, some love feel and sound of the car as you drive it. The same is true of our students. Asking them to all get the exact same message from a book (especially novels) is absurd. When you ask a student to write about the symbolism in a novel, but he is unable to come up with the same answers you think he should, you punish him for writing (not reading), making him multiple times more likely to despise his next writing assignment.

[pullquote align=”left” textalign=”left|center|right” width=”30%”]Find out what the students want to write about, and then have them write about it.[/pullquote]

There is a movement among colleges and high schools to let students read the books they want to read as opposed to dictating an assigned book from a district-defined list of classic literature. While I do not want to discuss the merits of studying the “Classics” here, I do want to point out that in these cases, the schools have found that students complete reading assignments more thoroughly and with increased displays of comprehension than with the pre-determined classic works. Since reading and writing are so obviously connected, does it not make more sense to let students write about the things they care about? Warlick suggested “authentic assignments” that have a real audience as a way to get the students to care about what they are writing. This is but one way to illicit “compelling writing.” Another, much broader, way is to simply find out what the students want to write about, and then have them write about it.